History Story

The following history of the Insulators Union was developed in to celebrate our 100th Anniversary.

The Year That Was…

Modern day historians view the year 1902 as marking a pivotal shift from a mostly agrarian society with limited manufacturing capability to an industrial era in full swing.

Indeed, the same year that our International Union was born marked perhaps the singular most important development in the birth of our nation’s–and the world’s–ability to produce materials and goods efficiently and on a large scale.

That development was what is now known as the assembly line, which made mass production possible.

Among the major developments of the 20th Century–human flight, electric power, the radio and television, telephones, and the computer–perhaps none are more significant than Henry Ford’s application of assembly line techniques to produce the first Model A automobile that rolled out of a Detroit factory on June 16, 1903.

The Model A sold for a seemingly extravagant price of $850 at a time when the average middle-class family income was only $1,200 annually, less than $20 of which was spent on recreation and entertainment. The cost of a horse-drawn buggy with steel wheels, by comparison, was $31.85. Only 1500 Model A’s were produced and snapped up by the very wealthy “in any color you choose as long as it’s black.” But its successor. The Model T became the realization of Henry Ford’s dream of an affordable mode of mechanized transportation for the masses. Over 15 million of these “horseless carriages” were produced. In a very real sense, assembly line production — first utilized om 1903 — literally put the world on the road to virtually unlimited potential in transporting goods and services that have brought prosperity and opportunity to ordinary people. It made possible the rapid transport of people, goods and services without the restricted dependency on footpath, bicycle, rail, horse-drawn contrivances and ferryboats.

It is hard to imagine the inconveniences, lack of sanitation, back-breaking toil, forced child labor, lack of health care and the attendant shortened lifespans that preceded the advent of steam, the development of the assembly line and the expansion of transportation and communication systems.

At the turn of the century, horses remained so prevalent that every day in New York City, 2.5 million pounds of horse manure was deposited on the city’s streets.

At the same time, 60 percent of Americans lived in rural areas, but by 1903 they were streaming into cities, leaving farms for factories. Additionally, masses of immigrants flowed through Ellis Island to transform the mix of the people that made up the nation, recasting the nature of American life. “By 1903, Americans were clearly industrialized,” writes Jeff Cannon, business history professor at the University of North Carolina.

“Out with the old and in with the new’ might be too strong a way to put it, but there’s no question what happened,” concurs Richard Tedlow of Harvard Business School.

In addition to the Model A, another mechanized for of transportation came into being in 1903.

Because bicycles had been so popular at the turn of the century, neighbors Bill Harley and Arthur Davidson, who worked for the same Milwaukee metal fabricator in 1903, used their skills as machinists to introduce the first Harley-Davidson motorcycle.

That same year, CB waterman of New Haven, Connecticut, came up with the idea of applying Harley-Davidson concepts in developing a portable motor for use on recreational boats. His ideas worked and eventually were perfect by Ole Evinrude, also of Milwaukee and famous for the Evinrude “outboard motor”.

By the time 1903 came to a close, Dayton, Ohio, brother Wilbur and Orville Wright were tinkering in their bicycle shop applying motorcycle concepts to power a “lighter than air” vehicle. On Dec. 17, 1903, in 27-mile-per-hour winds, they launched their test craft on the open sands of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Orville flew for 12 seconds followed by an astounding 59-second-long flight of 852 feet accomplished by brother Wilbur.

Other achievements and conditions, both significant and historically interesting, mark the year 1903.

The first trans-continental automobile trip was accomplished– a testimony to Henry Ford’s vision and the era’s embracing of technology. The trip from New York to San Francisco took 52 days.

Guglielmo Marconi completed the first two-way wireless message–a 54 word greeting to England’s King Edward VII, who responded.

Charles Curtis developed the steam turbine generator, which for the first time allowed electricity to be produced inexpensively. Meanwhile, geothermal heat was harnessed to produce electricity in Italy.

Edwin Binny and Harold Smith came up with an invention that would have an enormous impact on childhood: the crayon.

With great national pride, the United States settled a dispute with Canada to secure the southeastern border of Alaska and turned to begin construction of the Panama Canal.

Meanwhile, in Canada, Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier, known for establishing a transcontinental rail line in 1903, encouraged 2,00 English immigrants to cross into the prairies by wagon, foot and train following a grueling crossing of the Atlantic from Liverpool to St. John, New Brunswick. Under the leadership of Reverend Isaac Barr, they established the Barr Colony in the Province of Saskatchewan. This subsequently led to settlements in Alberta.

The population of Canada swelled to more than five million. By contrast, 80 million people populated the United States, then consisting of only 45 states. Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona, Hawaii and Alaska were territories.

A young Theodore Roosevelt was the first president to regularly be filmed and gave his famous “square deal” speech to farmers in 1903. His popularity as a strident anti-business, trust-busting crusader led to the creation of the Steiff “teddy bear”, representations of which have been cuddled by millions of children over the century. Americans regularly read The Saturday Evening Post and the Ladies Home Journal. The price of a postage stamp was two cents. Federal spending was only half-a-billion dollars. Unemployment stood at less than four percent.

The Kentucky Derby winner was Judge Himes; the NCAA football champions were the Princeton University team with an 11-0 record; the Boston Red Sox defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates five games to three to win the World Series. The U.S. Open was held Baltusal Golf Club in Springfield, New Jersey. Winner Willie Anderson shot a combined score of 307.

Edison Corporation filmmaker Edwin S. Potter made The Great Train Robbery, the first “Western” or cowboy movie, lasting 12 minutes and establishing the use of stills, motion and editing as a way to visually tell a story.

Pius X was Pope; helium was discovered; President “TR” sent the first message over the newly laid Pacific Cable; the Nobel Prize in physics was shared by Antoine Henri Becquerel of France and Pierre and Marie Currie of France for their mutual discovery and research into the phenomena known as radiation. Helium, an element rarely observed naturally in nature, was discovered.

The National American Woman’s Suffrage Association held its annual convention to push for women’s voting rights; two Irish-American women–Mary Kenney O’Sullivan and Lenora O’Reilly–established the National Women’s Trade Union League, formed with the goal of improving working conditions for women.

Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky published his theory of rocket propulsion after observing Chinese peasants propel object by compressing solid fuel into gas under pressure–in other words setting off aerial fireworks.

Rebecca Sunnybrook Farm, a beloved children’s classic about a farm girl and her six sisters, was written by Kate Douglas Wiggens; Pelican Island in Florida and ancient wind caves were added to the National Park System, protecting bird species in the southeast and a natural wonder in South Dakota, also allowing for the reintroduction of bison, pronghorn antelope, and elk.

There was a serious outbreak of typhoid fever in New York City and interesting weather, including eight hurricanes, one of which struck the coasts of Florida, Alabama and Georgia and another the coast of Pennsylvania. Meanwhile flooding in the U.S. did $3.4 billion in damages. A cold winter saw a record low of zero degrees on the North Carolina coast. A hot summer pushed temperatures to 102 degrees in such geographical separated areas as Colorado, North Carolina, and Wisconsin.

Meanwhile , there were 10 earthquakes recorded on magnitude 7 on the Richter Scale; and the electrocardiogram was invented and used for the first time to detect irregularities in the human heart.

New Years Day occurred on a Thursday; Christmas on a Friday; and our union came into being on a Tuesday.

That was the year that was.

We Celebrate Our Past As We Build for the Future…

The Advent of Steam Power

The members of today’s International Association of Heat and Frost Insulators and Asbestos workers trace the history of their union to the earliest days of the modern industrial era.

As the 1880’s drew to a close, much of America’s manufacturing and production activities were little more than cottage industries or small plants that relied on tedious manual labor using muscle power to turn out products one by one at a snail’s pace.

Hand-operated bellows kept forges at sufficient temperature to work metal into usable shape. Public buildings, manufacturing facilities and personal dwellings relied on wood or coal-burning fireplaces to takes the edge off winter’s chill. Only small windows and oil or gas lamps supplied light. Working conditions were barley tolerable in these cold, drafty and dim structures. The techniques of mass production were unknown and even impossible during those days.

However, in the closing days of the Nineteenth Century conditions changed dramatically and almost overnight. Steam power overtook the nation in much the same way that electricity would 40 years later.

Widespread use of steam power in this era resulted in better-heated, more efficient industrial plants and created untold thousands of manufacturing jobs. Working condition in factories improved and even living conditions in many homes were improved with the installment of steam heat.

Steam-powered machinery and processes significantly reduced the muscle and eye-straining tedium of hand operations.

With the introduction and rapid utilization of steam power an entirely new industry was created–the application of insulation to conserve the precious heat being piped from boilers into factories and offices, schools, homes and apartments across the nation, especially in the centers of industrial growth.

Foresighted workers saw a great opportunity for employment and job security. Many turned to the craft of applying insulating materials.

Those early mechanics who provided the craftsmanship for such a large undertaking were, at the time, mostly independent tradesmen or employees of small firms. For the most part, they lacked any form of cohesive or organized representation. They enjoyed no benefits or assurance of uninterrupted employment. Wage rates were not standardized and formal training in proper application was lacking.

Only a few insulation mechanics were fortunate enough to band together into small, localized associations that attempted to look after the interests of their members in specific cities.

Organizing Becomes a Necessity

The dawn of the 20th Century was marked by a turbulent era of economic depression, employer disregard for worker rights and government advocacy of strikebreaking. The need for working men and women to band together was inescapable.

The American labor movement was born and insulation mechanics were in the forefront of workers’ efforts to organize for their mutual protection and advancement.

The few insulators’ associations that had sprung up in major population centers attempted to form a national bond in 1900. This early effort was spearheaded by the Salamander Association of New York City, which took its name from the creature that, according to legend, had a skin that was impervious to fire.

The New York City association sent out an appeal to related crafts of other cities to form a “National Association of Pipe and Boiler Coverers.” This initial effort by the Salamander Association’s Joseph A. Mullaney and John Boden fell short of its goal, but certainly fueled worker sentiment for mutual collaboration.

Just two years later, the organizing effort was renewed through action by the officers and members of the association now known as Pipe Coverers Union 1, St. Louis, Missouri.

Local 1 sent out an announcement that it had affiliated with the newly formed National Building Trades Council of America and invited other pipe coverer associations and related trades to join with them.

Declaring “strength comes from unity,” the brother of the St. Louis local went about the task of forming a national union in a reasoned and methodical manner. The first appeal for unity was sent to targeted cities where other insulation mechanics had organized at the local level.

New York, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Boston and San Francisco responded to the call from St. Louis to recommend names of brothers who would form an “International Committee” to explore the formation of a national union.

An exchange of local union constitutions and by-laws also resulted from that call.

The Birth of our Union

With the St. Louis local leading the way, the interested locals who had responded to the call for the formation of a national union met for their first convention on July 7, 1903.

Local 1 President J.W. Shearn called the convention to order. The results were impressive.

A constitution was drafted and approved; by-laws were adopted; A.J. Kennedy of Chicago was elected the first president of the organization; and an assessment of the $1.00 per member was levied on each local union to pay expenses of the convention.

The following year–1904– brought with it even faster advances for the new union. At the annual convention, a formal name was adopted–the National Association of Heat, Frost and General Insulators and Asbestos Workers of America. And, on Sept. 22 of that year, the American Federation of Labor issued an official charter designating the Asbestos Workers as a national union.

The Early Years

The early years of the new union mirrored the time in which it was born. The United States and Canada at the turn of the century were trying t o struggle out of the depths of a severe depression that persisted even in the face of substantial industrial expansion. At the same time, a virulent anti-union sentiment among employers guided their hiring policies and working conditions. The federal government, when called upon to intervene in labor-management disputes, did so most often to the sole benefit of employers. And the public at large, along with many workers, were openly skeptical of a national labor movement that was still in its infancy. Even so, our union’s early leaders persisted in their efforts. By the 1905 convention, provisions were made that guaranteed each local would commit itself to the national policy of growth and strength through organizing.

Over the course of the next few years, membership fluctuated with 300 in 1905 to triple that number in 1910 with membership growth reaching 1,000.

Then, several Canadian associations added their strength to the American brothers and the fledgling organization to the AFL, asking for a charter with a change of name to the International Association of Heat and Frost Insulators and Asbestos Workers.

The goals of the new International were spelled out in the charter subsequently granted by the AFL:

“The object of the International Association of Heat and Frost Insulators and Asbestos Workers shall be to assist its membership in securing employment; to defend their rights and advance their interests as workingmen; and by education and cooperation raise them to that position in society to which they are justly entitled.”

The new AFL charter also specified the work over which the Asbestos Workers would have jurisdiction as the “practical mechanical application, installation or erection of heat and frost insulation such as magnesia, asbestos, hair felt, wool felt, cork, mineral wood, infusorial earth, mercerized silk, flax fiber, fire felt, asbestos paper, asbestos curtain and millboard or any substitute for these materials engaged in any labor connected with the handling or distributing of insulating materials on job premises.”

When the asbestos workers met in convention in 1914, Joseph A. Mullaney — who had been a part of the effort by the Salamander Association 14 years earlier — was serving his first term as president of the International Union. His report to the delegates included the heartening news that the membership rolls had grown to almost 1500 and the number of affiliated local unions stood at 19. (Mullaney was to go on to subsequent terms covering a period of 43 years during which membership continued to grow.)

By the time the International held its convention in 1917, the good news of continued expansion and work opportunities for the membership was tempered by the cold reality that the United States had entered World War I. The dark days or war, in which the nation mobilized all of its domestic resources to defeat the enemy in Europe had created an urgent need for the skills of Asbestos Worker craftsmen.

From Boom to Bust and Back

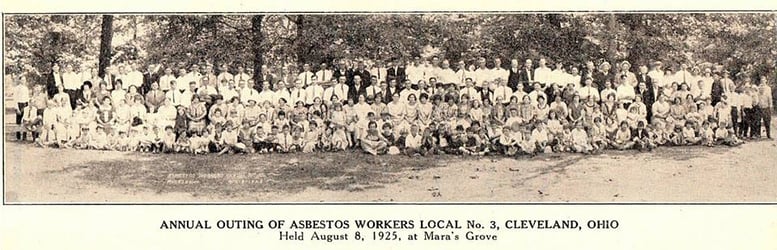

The union, like all building trades, was poised to enter the 1920’s in a position of strength. The war meant economic boom times for the construction industry. Existing local unions expanded and new locals were formed within our organization despite the redoubled but unsuccessful efforts by anti-union employers to break the backs of unions.

But the boom was bound to end and the construction industry fell flat as the stock market crashed in 1929. “Black Friday” stretched into a black decade as all American and Canadian workers suffered the worst economic hardship ever encountered. With little work available, every union was decimated and only the strongest survived–a testimony to the determination of our own union’s leaders who kept our organization alive during these bleak times.

War again raised its ugly head. When America went to war in 1941, the nation was ill equipped to arm or supply transport its fighting forces. A massive domestic effort was required to bring our armed forces up to muster, particularly in rebuilding a Navy that had suffered an enormous destruction at Pearl Harbor. The craftsmen of the Asbestos Workers responded to the challenge and played a crucial role in the reconstruction of the U.S. naval forces. (In a little known footnote to history, all but one of the major vessels sunk at Pearl Harbor were refloated and rebuilt thanks in large part to the skills of Asbestos Workers engaged in shipbuilding and repair.)

At the end of World War II, the United States and Canada again turned to the task of domestic construction. The earlier experiences of the previous generation of craftsmen were repeated in that the International gained new members by the hundreds and all enjoyed a new era of prosperity.

Under the leadership of General Presidents Carlton Sickles, Hugh Mulligan and Albert Hutchinson, membership reached a pinnacle of just over 23,000 as existing local unions broadened their apprenticeship programs and opened their doors to new members. New local unions were chartered and our organization was poised for unprecedented expansion of the nation’s infrastructure and to meet the challenge of a new era– the dawn of the nuclear power industry and the need to expand our nation’s energy base.

The Modern Era Dawns

Turbulent times lay ahead for both the United States and Canada. A controversial was in Southeast Asia in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, a severe energy shortage with attendant long lines for scarce gasoline and soaring prices for all fuels, economic downturn and high unemployment in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, union-busting national policy of the Reagan-Bush era and social upheaval throughout all three decades took their tool on both America and Canada in general and on organized labor in particular.

By the 1980s, the pendulum again began to its swing back to a decline in union ranks and the ability of workers to gain through collective bargaining and political activism.

And out union faced even greater challenges.

Frightening new evidence had come to light, confirming long-held suspicions by our International’s leadership.

For years Asbestos Workers had sought hard, positive proof of what they suspected to be true–that workers who were exposed to asbestos died in hugely disproportionate numbers from cancer. It would take many years of argument, industry and government denials and research supported by our own union to finally gain worldwide medical acceptance of the link between asbestos and disease.

Under the leadership of the late General President Andrew Haas, our union formed a unique alliance with the medical community, particularly with Dr. Irving Selikoff of the Mount Sinai Center for Occupational Medicine.

Through memberships screening programs sponsored by our organization and union-funded research at Mount Sinai, the facts proved to be even worse that had been suspected.

Medical evidence now conclusively proves that exposure to asbestos fibers produces an extraordinarily high risk of contracting cancer. In fact, studies have shown that one of every five workers exposed to asbestos died of lung cancer in one form or another. Often times, the diseases related to asbestos exposure do not show up for 20 to 40 years after exposure.

Thanks to the alarm sounded by our union and the continued research–much of which continues to be funded by our own membership–the medical community, industry and government now recognize the danger and have adhered to union recommendations, enact and enforce regulations to minimize exposure in the future, not only for asbestos, but for many other carcinogens that have been identified as routinely used in construction.

Following the lead of General President Haas, his successors William G. Bernard and our current General President James Grogan have kept the issue of members’ health on the front burner. Our union continues to work with the medical community, the AFL-CIO, the Building and Construction Trades Department through its Center to Protect Workers’ Rights as well as with labor-friendly legislators to further strengthen worker safeguards and to assure that exposed workers receive adequate and just compensation when disease develops.

Our Union Today

Early in the 1990s a new threat reared its ugly head–a downturn in market share previously enjoyed by union construction workers and a falling membership due in large part to anti-union legislation and ab open shop sector that will leave no stone unturned in its effort to take decent jobs and wages away from union members and fill those jobs with low-wages away from union members and fill those jobs with low-wage workers with few if any benefits and little or no training.

Under the leadership of William G. Bernard and out current General President, James Grogan, we enter out second century with bold new initiatives to counter the treat to our new membership strength and our market share.

With the wisdom and foresight of delegate to out 1997 and 2002 General Conventions, our union is making significant progress in the area of organizing within our industry and expanding our jurisdiction in such areas as hazardous material abatement and firestopping — an area of work we have claimed since the advent of the nuclear power industry almost 40 years ago.

Under the direction of General President Grogan, our organizing efforts have achieved significant growth in membership and man-hours worked and organizing continues to be a top priority of our union and a mandated policy requiring COMET training and full participation on the part of each and every member of our organization, including new members taken into our ranks.

Meanwhile, our union has fostered the creation of a new level of cooperation with our employing contractors through support of a newly formed all-union contractor alliance. Working with these union-only contractors, our union is prepared to strengthen the competitive edge for our employers, enabling them to go after work such as firestopping and expansion of electrical generating capacity for our nation.

One of the most exciting developments marking the close of our first one hundred years has been the purchase, renovation and occupancy of a headquarters building that, for the first time in our history, is a home for General Office administration that is fully owned and controlled by our union.

Previously, our organization had occupied rented space in several different buildings in an increasingly congested area of Washington, D.C. Thanks to the efforts of General President Grogan and our General Executive Board, this situation came to an end.

The move to our own building in near-by suburban Maryland occurred early in 2002 and a formal building dedication occurred on May 1, 2002. The gala affair was attended by hundreds of International and local union representatives, contractors, family members and friends of our International Union.

Another event of great significance occurred later in the summer of 2002 as approximately 400 delegates from across the United States and Canada gathered for our International Union’s 28th General Convention. The delegates gathered to strengthen programs and policies that have proven to be successful and to inaugurate bold new steps to take our union into a new era of growth and prosperity.

The delegates elected a slate of officers to guide our union into a second century of progress, building upon a proud legacy of past achievement and embracing great optimism for an even brighter future in the years to come.

Elected were General President James A. Grogan; General Secretary-Treasurer James McCourt; and International Vice Presidents George Snyder (Mid-Atlantic States), Roger Hamilton (Western States), William Mahoney (Southeast States), Harvey Hartsook (Midwest States), Kenneth Schneider (Southwest States), Gary Fujawa (Central States), Fred de Martino (New York- New England States) and Canadians Anthony Ceraldi and Andre Chartrand.

In addition, Brother Terry Lynch was elected to fill a vacancy created by the retirement of Jack Keane, who had served with great distinction as International Vice President At-Large and our union’s expert in safety and health issues.

And delegates accorded the high honor and title of General President Emeritus to William G. Bernard, who had retired the previous September after more than 40 years of service to our International Union.

Sadly within a few months following the 2002 Convention, our International Union lost two of its most beloved leaders: Roger Hamilton and George Snyder, both of whom succumbed to asbestos-related cancer.

Subsequently Brothers Doug Gamble and (Terry Larkin) have been respectively elected to fill the vacant vice-presidential positions.

On a Final Note

Throughout the years, our members have faced adversity in one form or another. But we have persevered with the guidance of strong leaders and the united efforts of our new members. We have come a long way in the past 100 years. Because of the endurance of our first members and their relentless pursuit for a higher standard of living and better benefits and conditions, our members today enjoy a safe workplace, good hourly wages, superior health and welfare benefits and a generous pension.

Just as those early founders set in motion events of historical proportion, so too, will the leaders and membership of today do as they pave the way for a second century of pride and accomplishment.